Spring 2024

2

The Blind Love of Language:

Discovering Poetry in the Everyday

Kelli Russell Agodon (Faculty)

The Blind Love of Language:

Discovering Poetry in the Everyday

Kelli Russell Agodon

Faculty

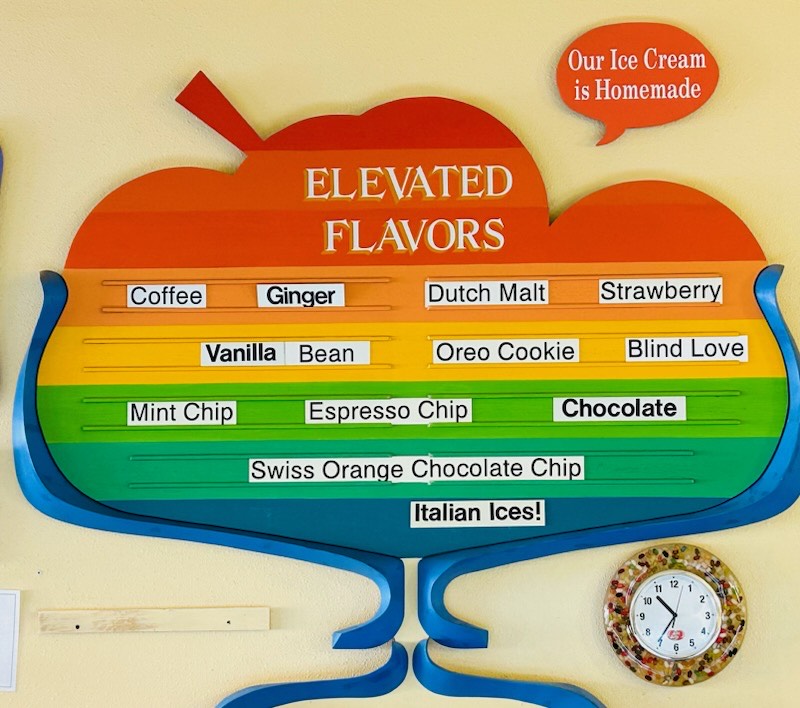

Recently, on a day I had set aside for writing, I found myself changing plans and deciding instead to accompany a friend to an ice cream store in Port Townsend. While he quickly chose Swiss Orange Chocolate Chip, I paused, unsure. I was feeling a little guilty for not staying home to work on my poetry manuscript, and eating ice cream was feeling a little frivolous in comparison to the “real work” I should have been doing. Unclear what I wanted, I started reading the list of all their different ice cream names—praline, chocolate, mint chocolate chip, vanilla bean, blind love . . . wait, what? Blind Love? Was that an actual flavor or had someone mistaken the sign for a jukebox playlist? I leaned toward the woman with the cherry earrings working behind the counter and asked, “What is Blind Love? May I sample it?” Occasionally after saying something, I feel as if am living inside a line from a poem. This was one of those moments—Yes, I’d like a scoop of blind love.

As someone who can devote hours, even an entire week of a writing residency, to writing and revising, sometimes I have to remind myself to ease up, get outside, and explore. I forget how there is a world of poems waiting for me in every moment of my day if I just pay attention. As Naomi Shihab Nye wrote in her poem “A Valentine for Ernest Mann,” poems hide. In the bottoms of our shoes, / they are sleeping . . . What we have to do / is live in a way that lets us find them.

As a writer and editor, it can be easy for me to stay indoors trying to nail moonlight to my desk, or as others call it: writing a poem. As Carl Phillips wisely observed in his book of essays, My Trade Is Mystery: Seven Meditations from a Life in Writing, “sometimes the problem is that we’re trying too hard” and “distractions can be useful.”

As a younger poet, I believed the best poems stemmed from significant events—a trip to Italy, a major news story, a birth, a death—and yes, many do. But after enjoying a cone of Blind Love, I'm appreciating the everyday nature of poems and how if we stay present and observe the world and words around us, we can often stumble upon them (or their beginnings) in the most ordinary of spaces. For example, in February 1962, on a ferry ride to Staten Island for a poetry reading with Robert Lowell, Frank O'Hara read a newspaper with a headline detailing Lana Turner's hospitalization for exhaustion following her collapse at her forty-second birthday celebration. O'Hara, inspired by the headline, wrote the now-famous poem, “Lana Turner has collapsed!” while traveling to the event. He even read the newly penned poem at the reading (to Lowell’s displeasure). Lexi Pelle wrote “The Bats Are Having Non-Penetrative Sex in a Church” after reading an unexpected science article on CBS News. She wrote: “When I read the story . . . I knew it needed to be in a poem. It made me laugh, but also made me think about the lengths (pun intended) scientists will go to understand the world’s mysteries, which feels related to the process of writing poetry.”

Even a good typo or mishearing (a.k.a., mondegreen) can inspire new work. Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Man-Moth” was inspired by a typographical error in a newspaper. What was originally meant to be “mammoth” turned into one of her most read poems. In her 1962 essay “On ‘The Man-Moth,’” Bishop wrote, “. . . the misprint seemed meant for me. An oracle spoke from the page of The New York Times, kindly explaining New York City to me, at least for a moment.” Another well-known example is Thomas Lux’s poem “I Love You Sweatheart,” inspired by misspelled graffiti Lux saw on a girder above the highway he was driving on. “How Killer Blue Irises Spread,” a poem I wrote as a graduate student at RWW, emerged from mishearing an NPR news report about “how killer flu viruses spread” as a nervous young mom. Recently, Susan Rich’s poem “Temporary Madness” came to be after she wrote an email and a Facebook post about a recent break-up where a caring friend misread “break-up” for “break-in.” Rich begins her poem with: “I hope the break-in wasn’t too bad, Marianne offers / misreading in for up . . .”

Surprisingly, even the distraction of the internet can be a source of new work; there are several poems inspired by tweets. Maggie Smith’s well-loved poem, “Poem Beginning with a Retweet,” began with just that, a retweet that read: If you drive past horses and don’t say horses, you’re a psychopath. Two of my poems were inspired by tweets: one from Shaun Cassidy (yes, that Shaun Cassidy), “There is too much beauty in the world,” which opened up a conversation on the environment and wildfires in the Northwest, while another from a stranger’s tweet, “If you had a mermaid phase as a kid, you’re probably bisexual now,” offered a door into an earlier self on a subject I had never written about.

“Surprisingly, even the distraction of the internet can be a source of new work; there are several poems inspired by tweets.”

Courtney LeBlanc used a question on Twitter, “Would you ever get your spouse’s name tattooed?” as her title and responded to the complexity of the question to explore a situation where an ex calls to say he got the speaker’s name as a tattoo as “a testament” to their time spent together. Katie Manning, inspired by Todd Dillard’s tweet “I think everyone in the poetry community deserves their own moon,” wrote the poem “Choosing a Moon.” Todd Dillard, inspired by a tweet by Matt Coyne, shared on Halloween about his kid: “I have felt uncomfortable before. But we were just passed by a slow moving hearse and funeral cars . . . My son is dressed as the grim reaper. He f**ng waved,” which prompted Dillard to write and share the poem “Dead Drive” to explore what it would be like to meet death. Hannah Stephenson wrote the poem “Fraction” off of a Jimmy Kimmel tweet, “One day, my heart will stop beating. (not everything is a joke).” When the poem was published, she shared it, and Jimmy Kimmel retweeted it, bringing it all full circle.

Inspiration came from Facebook posts for Heidi Seaborn’s ecopoem “Catalogue of Hungers and Hopes,” which was sparked by reading a post—“the worst thing for the environment is to have a child.” Her poem even incorporates a note from a friend: “If the universe had an ICU, the earth would be in it,” reminding that lines for poems can arrive via text message. My good friend, Martha Silano, sent me a text from O’Hare Airport, which autocorrected to “Stuck in O hate airport!” to which I texted back, “You need to write that poem!” Martha did write that poem and “Ode to Autocorrect” was quickly picked up by Poetry Magazine. As someone who is more than happy to give you her own personal TEDx Talk on the importance as a writer of avoiding social media and turning off our devices, sometimes having a more open perspective on the gifts and benefits of material in all aspects of our lives can be important—including when we’re on the internet or playing around on our phones.

It is cliché to say, “Inspiration is everywhere,” but daily I am reminded that it is. But these examples do more than just notice, which is the initial step of the creative spark: they also accomplish two even more crucial tasks—remembering the moment and writing the poem. I think back to that moment in the Port Townsend ice cream store and the curious discovery of “Blind Love” (which is triple chocolate, by the way). I found not just an amusing distraction, but a poetic metaphor. Finding material can resemble blind love: an inexplicable and unquestionable attraction to words where we fall in love with new ways of discovering the poems around us. Encountering these moments of inspiration in our everyday lives—be it through typos, headlines, or even ice cream flavor names—I’m reminded of the surprise and serendipity in the ordinary where even the briefest of moments can provide us with potential material. Being observant turns our everyday experiences into an opportunity for new work, and our world opens through our writing lives—like uncovering magic in the simplest things, such as an ice cream flavor that unexpectedly ignites a poem, or perhaps, even an entire essay.

Kelli Russell Agodon is a bi/queer poet and editor whose newest book, Dialogues with Rising Tides (Copper Canyon Press) was named a Finalist in the Washington State Book Awards and shortlisted for the Eric Hoffer Book Award Grand Prize in Poetry. She is the cofounder of Two Sylvias Press, where she works as an editor and book cover designer. She recently published Demystifying the Manuscript: Essays and Interviews on Creating a Book of Poems, which she co-edited with Susan Rich. Kelli lives in a sleepy seaside town in Washington State, where she is an avid paddleboarder and hiker. She teaches at Pacific Lutheran University’s low-res MFA program, the Rainier Writing Workshop, and is currently part of a project between local land trusts and artists to help raise awareness for the preservation of land, ecosystems, and biodiversity called Writing the Land. She also cohosts the poetry series "Poems You Need" with Melissa Studdard.

www.agodon.com / www.twosylviaspress.com / www.youtube.com/@PoemsYouNeed