Fall 2022

3

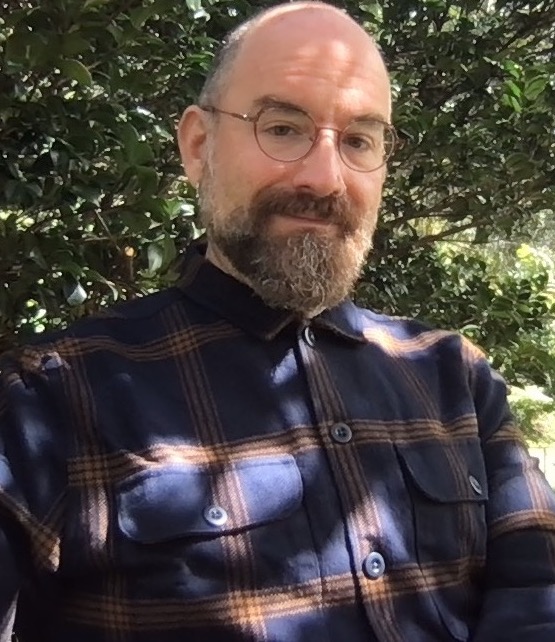

How to Define Care?—An Interview with Brian Teare

Hannah D. Markley, Contributing Writer (Class of 2023)

How to Define Care?—An Interview with Brian Teare

Hannah D. Markley

Contributing Writer

Class of 2023

This summer, we welcomed two new faculty to the PLU campus. One of those faculty is 2020 Guggenheim Fellow Brian Teare. He is the author of eight chapbooks and six critically acclaimed books, including Companion Grasses, a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Award, and Doomstead Days, winner of the Four Quartets Prize and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle, Kingsley Tufts, and Lambda Literary Awards. His most recent publication is the 2022 Nightboat reissue of The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven; his seventh book, Poem Bitten by a Man, is forthcoming in the fall of 2023.

Brian and I held our conversation over email, and I’m glad to share it with you here.

~

Hannah D. Markley: You grew up queer in Alabama, and after time in cities on the West and East Coast, you’re now at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Which places sustain you at this moment? Which places from your past do you return to in your writing? How do these places teach and/or influence your work?

Brian Teare: This is a generous, layered question. In terms of my education as a poet, the queer and literary communities of the San Francisco Bay Area remain essential to my expanded sense of and continued faith in poetry’s possibilities. During the thirteen years I lived there, I was introduced to the boundless potential of experimental poetic forms, learned to letterpress print and hand-bind books, participated in the gift economy of small press poetry publishing, and came to love the crackling energy of dialogue with queer and feminist peers and elders outside of academic institutions. Speaking to my life as a creature on this Earth, I carry everywhere with me in different ways, in part because in each place I’ve lived I’ve learned to do a different kind of work. From my rural childhood, I learned to be intimate with habitat in a daily way; from Northern California, I learned traditions of ecological writing, bioregional poetics, Buddhist thought, and environmental politics; from Philadelphia, I learned to practice intimacy, ecology, bioregionalism, Buddhism, and environmental politics in an urban environment; and in Virginia, I am learning to read in the landscape the intertwined histories of settler occupation and enslavement that shaped and continue to shape place and public policy in this country. Everywhere, I aspire to write from a holistic sense of being here together, human and more-than-human, interdependent and vulnerable. All of these places, communities, and conversations inform and sustain the way I write and teach now, which remain mindful practices, always evolving.

HDM: I love this notion of “carry[ing] everywhere with you” and how those places and their lesson grow with you. It’s definitely evident in your work. Who have been your human mentors, and how have they shaped your approach to mentorship?

BT: For a long time as a young writer, I felt I wasn’t being and hadn’t been mentored the way I wanted to be. Later I learned this is a feeling common to young writers, and I came to understand that a fantasy of “ideal” mentoring often kept me from experiencing and fully appreciating the ways I’d been so generously mentored throughout my writing life. Now I count myself lucky. There were crucial one-on-one mentorships during my BA and MFA in which faculty mentors read my shitty drafts, gave encouraging advice about revision, helped me to see what to save and what to throw away, and sent me to the library with lists of books I should read. After my formal education, as I struggled to make a life as a writer, a few elders in the poetry community took me to lunch and sent me home with leftovers—these same people sometimes invited me to give a reading or offered me adjunct teaching gigs, generous gestures that put me in community and kept me afloat. But my most treasured mentor was the poet Jean Valentine. Her mentorship was less about my poetry and more about being seen as a poet and person struggling to find a place in the world. The hours we spent drinking tea at her kitchen table remain precious to me for the deep quality of her listening and the reciprocity of our care for each other. The first time she asked me to read her poems in process, I was honored and humbled by her trust; she was the only mentor who invited me to be a peer in precisely that way, whose mentorship became true friendship. I miss her immensely. Now, I hope that my own mentoring employs aspects of all these relationships—when appropriate, at the right times—writing and revision guidance, reading advice, practical support, and deep listening.

HDM: What a gift to be trusted with her writing! Apart from mentoring, how do you hope to contribute to and learn with this community?

BT: I join the RWW community with respect and enthusiasm for the ways it centers care as the core of its pedagogical spaces. The challenge remains: care is defined entirely in relation, and what constitutes care for one person does not feel like care for another. Not only do our individual needs differ, but we might not always know what kind of care we actually want or need, what kinds of care to which we best respond. So, I hope to continue to learn better how to listen deeper into each relation, how to define care in each relationship at RWW, and how to negotiate and pivot between multiple modes of caring as mentor, poet, and literary citizen.

“The challenge remains: care is defined entirely in relation, and what constitutes care for one person does not feel like care for another.”

HDM: I would guess care, its necessity and questions, drew many of us here. Speaking of intention, what hobby or routine do you keep outside of writing?

BT: As I think most everyone in the community knows, I run Albion Books, a micropress dedicated to poetry and hybrid writing. When I’m not researching and writing my own poems and essays, I edit manuscripts by other poets and inter-genre writers and digitally typeset them, then I set type by hand, print covers on a Kelsey table-top or Vandercook press, desktop print and fold and collate text blocks, and then bind the chapbooks with a needle and thread. I do all this while privileging upcycled and recycled materials, which adds another layer of creative constraint to the process. I love the meditative labor of binding, and I also love the feeling of all the parts of the chap—all the steps of planning and publishing an edition behind me at last—coming together on the binding table. Micropress publishing is a really satisfying form of service to the literary community and a small way to participate in the long tradition of poet-printers and poet-publishers whose labors created literature and literary community as we know it.

HDM: What writing projects are you working on currently?

BT: Over the summer I worked on the reissue of my 2015 book, The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven, which will be out this month from Nightboat. And I’m currently finalizing the text of my seventh book, Poem Bitten by a Man, which is a companion to The Empty Form. It will be out in fall of 2023, also from Nightboat. Albion is running on all cylinders, with chapbooks by Christina Davis and Miranda Mellis in various phases of production. Davis’s Neighborn should be out this fall, and Mellis’s The Revolutionary should be out in the spring—unless the opposite turns out to be true!

HDM: Many congratulations! Before we wrap up, is there anything that I haven’t asked that you want to share?

BT: For those that care, I’m a double Scorpio, with my moon in Sagittarius. People like to say, That explains a lot. And I like to choose to take that as a compliment!

HDM: As you should—thank you so much for your time and work with RWW, Brian.