Curious Gifts: Remembering Judith Kitchen (1941-2014)

_

The apple trees in the yard behind our house have blossomed so that, waking, I look into a sea of white clouds. I could go back to apple trees, the peculiar branchings that make for good climbing, my mother’s voice calling me down.

—Judith Kitchen, The Circus Train

A man measured a closet to make sure the bookshelf would fit. He pulled the heavy shelf into the room on a rug to save his back. His wife directed from her bed. He was happy to do it, grateful for these moments. White hair hung in his eyes as he arranged the books, per her instruction.

An orchestral piece played in his head, the same movement, over and over. He didn’t know she had planned ahead. Documents in order, things sorted through, donated. Discarded. In a few months, he will look for an anthology with an intricate cover, simply called Apple, that she had put together years ago. He will not be able to find it.

The bookshelf in order and to her liking, at least for the moment, he began to leave the room. She said, “I guess I should sleep now.” He leaned over to kiss her on the forehead. She was gone.

Judith’s husband, Stan Sanvel Rubin, refers to this moment as one of the curious gifts Judith gave the world when she left it in November 2014 after being diagnosed with cancer years earlier. Leave it to Judith. She took away the questions that the bereaved are often left with. She did not suffer in those last moments. She did not die alone. As Stan pumped her chest and waited for the ambulance to arrive, he knew she would be angered at his efforts—in control of herself even after death.

***

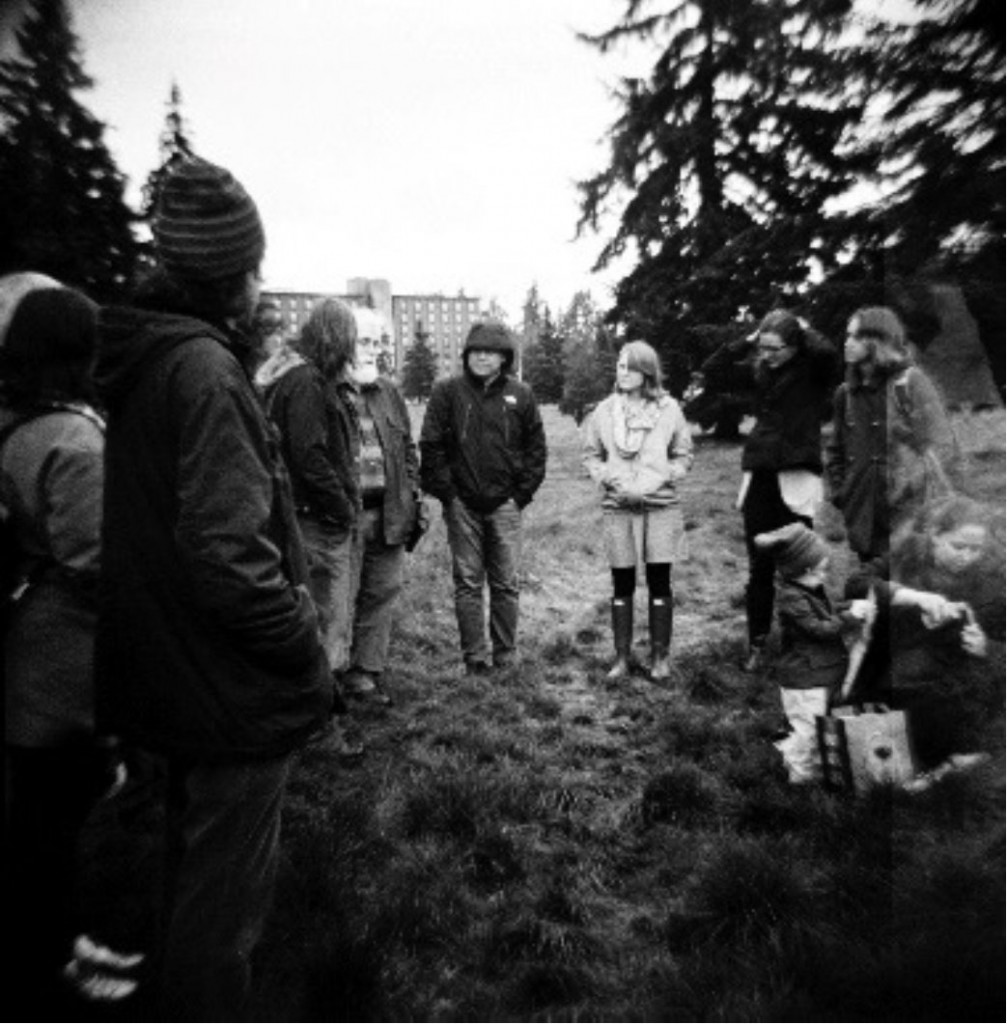

On a winter day in February 2015, four apple trees were planted in Judith’s memory on the third green of the Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) golf course. A small gathering of friends and loved ones, which included Stan, Judith’s brother George, her son William, Rainier Writing Workshop (RWW) Director Rick Barot, and RWW alums and participants, stood with their fingers deep in pockets against a gray, soggy day. The root balls of four different varieties of apple trees—Scarlet Sentinel, Cox Orange, Beni Shogun, and Pink Pearl—were sunk into the ground by gloved hands. Maple trees would have also been appropriate, as the fall foliage had always reminded Judith of the east coast where she grew up. But the apple trees—that’s what Stan said she would most want. Her brother George shared a story of how, when he and Judith were children, they stood side by side on a large apple tree branch as it slowly broke, as if it was trying to set them down as gently as possible.

Judith co-founded RWW with Stan, and it was the RWW graduating class of 2015 who gifted the trees for the ceremony. As I drove to the planting, I wondered what I might say. “Science Friday” was on NPR’s All Things Considered, and I listened as bee hives and flowering trees on the runways of the Seattle airport were discussed on the show. Words stuck in my mind—fruit, honey, grafting, pollination, bees.

Most apple trees are incapable of self-pollination. Several varieties are often planted within a hundred feet of one another so they may share valuable pollen needed to bear fruit. Most trees primarily depend on bees to achieve pollination. In the event of having only one apple tree, you can place a bouquet of another variety under the canopy of that sole tree—a deliberate gesture of encouragement, of hope.

***

As our apple trees for Judith bloom each spring, bees will visit the blossoms. And like the trees, Judith’s work and mentoring, her vision and love for writing will continue to pollinate all of us who share and respect her devotion to the craft. This brief and loving act will bear fruit for all those who have been and will be touched by her work and memory. She will live on, will pollinate future crops with her words. And she will continue to live in ours.

And the orchestral piece in Stan’s head? Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem,” a work commissioned to celebrate the reopening of Coventry Cathedral, which was bombed in World War II. The work combines the Anglican Mass for the Dead with the poetry of Wilfred Owen. Stan says Judith was clear that she wanted the final movement of this piece played at her memorial service. This last movement contains Owen’s line, “Let us sleep now,” as former enemies unite in friendship after death.

Sleep well, Judith.

Okay, so I’m not sure about some things, but others are decidedly crisp and clear. Like apples in October.

—Judith Kitchen, The Circus Train

This Is How We’ll Remember Her…

I would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to PLU for their support of this event. Kenneth Cote in Facilities was extremely helpful, and all involved were eager and kind to make this event special. A plaque bearing Judith’s name will be displayed in the University Center, and more memorial events will take place at this summer’s RWW residency.

It is impossible to include all those who loved Judith in this piece. The following memories and ruminations on apples and orchards from RWW faculty and alumni represent just a sliver of the voices who forever remember Judith.

I see her, the child Judith, climbing her favorite apple tree, near her house but not too near, far enough away so its branches embrace her privacy, its gnarled trunk leads her up up where she can see what others cannot. Her parents warn her not to climb when the trees are blooming, not to disturb petals that lead to fruit. But Judith knows how to step just right so she can hide among the blossoms and listen in on conversations drifting up from the earth. Judith among the branches, keeping still, watching ovenbirds zip, their rapid-fire teacher-teacher-teacher calls. Ovenbirds skitter on skinny legs, scatter the duff and litterfall of the forest floor, then bow tiny twigs up high, beyond her reach. Judith never disturbing their leaf-covered domes, but always looking, checking to see what has changed, what might be coming along. Judith among green fruit, impatient. October Judith in the time of ripeness climbing higher to fill her pockets with cold-hardy Northern Spies. Her teeth piercing the tender skin, first juice of the season sucked in, her hands sticky, the flesh crisp. Cut into chunks, stirred with brown sugar and cinnamon, picked apples folded into pastry shells become what bakers call apple blossoms. And so the cycle returns, begins again.

I hear over my shoulder Judith. Scoffing. Saying how much she hates the way people try to romanticize children. And apples. And ovenbirds. Saying how the orchard was neglected, how the bark ripped her skin. How nobody in her family baked. How her father was completely unsuited to making things grow. And yet she, the child in that tree, dug deep, planted with care, nurtured crops in each of us, crops that bore well, crops that fed bugs, crops we had to plow under. And Judith taught us all how to keep alive the branches we need, the secret places we need, the promises of leaf, bud, bird, silken fruit.

—Peggy Shumaker, RWW Faculty

***

I live far from Judith’s apple trees but am struck by reports of one of their names—Scarlet Sentinel. Imagine Judith saying the words. Scarlet. Sentinel. Relishing the sound, the ruddy color, even the embedded action, an apple tree that stands guard, on watch, but for what? Imagine Judith wondering, remembering, positing, repeating, in the way, as she liked to say, of the lyre.

When I worked with Judith I was aware of how she loved to name, and the voice of her critique was no less exquisite than that of her essays. Here are fragments of naming from her letters:

Voice, voice, voice. Structures that orchestrate (there’s no other word for it) the reader’s perception. Juxtaposition. Story emerges as collage, embodiment of memory. And perception. Always perception. Not chronology. Exile. That family does or does not function. That dysfunction spills over to, or comes from, locale, background, topography. The issue of grace. Fiery intensities. Linguistic acrobatics. Your imagination is really fired up right now.

She loved to name her experience of reading and she loved to name and rename form. We argued over what to call the form I was attempting then, a novella-length narrative essay. She insisted I name what I was doing. The word we landed on was “essella,” not a term that has caught on so far, but the sound of which I still think of tenderly and sonically, as spoken, perhaps, by some hot body in a tank top shouting up from a sweatier street. “Essella!” Okay, the hot body image is my perception, colliding with hers, and Judith would have said as much, in all her fiery linguistic acrobatics. Then again, can’t you imagine Judith sitting barefoot and cross-legged at the back of the auditorium, scarlet sentinel of us all, shouting out at the stage. “Essella!”

—Barrie Jean Borich, RWW Faculty and Alum

***

Can a person’s voice, alone and afloat, be the stuff of inspiration? The voice on the other end of the line seemed to come over the top of a hill rise and begin a full-throated rush. Slightly high-pitched but with an upstate scrape, the strong, womanly voice told me that my manuscript had been chosen in the State Street Press chapbook contest. Each editor chose one book and, in fact, the voice said she’d been the one to choose mine. It was to be my first collection, and as I stood looking out of my California farmhouse, not at apple trees but almond trees, I sounded both grateful for the award and unsure of what to say. The conversation went on, and I think I actually asked the editor to tell me again her full name. Judith Kitchen.

Later that year, my wife and I went east and Judith insisted that we meet for lunch at The Algonquin Hotel, its dining room famous for the raucous luncheon Roundtable at which sat—among many—the witty Dorothy Parker and The New Yorker editor Harold Ross. Judith’s voice greeted us as if we belonged at the famous table, and she quickly went into a happy disquisition about my chapbook. Then the conversation turned to what it eventually would every time I’d come to dine with Judith and her husband, Stan: the powerfully exciting if not precarious state of American literature. As anyone who knew her could attest, the volume of her incontestable assessments always carried the day.

Judith’s voice was the sound of imminent achievement. I’ve written elsewhere about her extraordinary writing, her voice on the page. For me, she was the teacher who didn’t need to line-edit my poems. She was the accomplished editor who included my early work in the big discussion. I realize now what I realized then: that the privilege of having been in Judith’s presence helped to form a foundational confidence enabling me to go beyond the work of that early collection.

—Kevin Clark, RWW Faculty

***

An apple tree—did Judith like apples? I don’t know, but it seems an apt metaphor for her. Judith Kitchen bore fruit again and again and again—in her own literary life and in the lives of others. In fact, even in her death, she continues to bear fruit for herself (Harvard Review posthumously!).

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Let me tell you how I met Judith. She and Stan were teaching at the University of Nebraska Writers Conference. I’d already applied to RWW, then enrolled for this conference as a back-up plan—in case Stan didn’t accept me into the program. I figured I’d meet them, schmooze them, and improve my chances for 2008 admission.

Except I got in—after it was too late to cancel Nebraska.

So there was Judith, in the basement of some University of Nebraska building, sitting cross-legged on a chair, a bemused smile on her face. Very literary Buddha. Many of you have heard the story of how awful that workshop was, how Judith waited for the class to police itself, how I couldn’t bear it and had to draw my sword, as it were, and restore order. How after class, Judith said, “What took you so long?” How I said she was the teacher and that I was waiting for her. How she said, “You should always let the class do the work. That’s your first teaching lesson.” Then she said, “We’re going to be friends, you and I.”

Every one of Judith’s literary successes she created herself. No one helped Judith Kitchen get recognized. And she didn’t expect it. But by the same token, she believed she could make it easier for others. A nudge here—“You know, if you just put this in reverse order…”—an introduction there—“I want you two to meet.”—a direct order sometimes—“Just finish the manuscript! Worry about its order once it’s finished.”

Judith fed me. Everything I know about running a workshop and most things I know about putting a manuscript together I learned from Judith. But perhaps best of all, Judith was my friend. I can hear her delicious laugh—partially hoarse and delighted into action by some unexpected phrase or idea. I’m sure you can hear it, too. And I see the ways we all have benefited because one woman planted a seed that grew into a tree that continues to bear fruit.

—Kate Carroll de Gutes, RWW Alum

***

“You’re too old for a conventional career,” Judith told me once, and I was a little offended until she explained: “It’s a good thing! It means you’re free to do what you want!” I think my response was terrified laughter, but I knew she was right. Where I saw an obstacle, she saw exactly the challenge she was looking for, or at least, one she could manage. Though I think she would say, if I could ask her now, what obstacle?

“The main problem for women is confidence,” she told eighteen women at the Centrum summer workshop where I first met her. Then she systematically demolished all our reasons for thinking we weren’t “real” writers yet. She showed us her latest anthology and told us we could write as well as anyone in it. She said she’d read many novice pieces that outshone the work of more famous writers. “You’ll see,” she promised, and over the course of the week, she helped us recognize our own best writing: our most honest, original sentences, the music and imagery that tapped into deep emotion. By the end, we saw the potential in our drafts, and were impressed with each other and with ourselves. I left with a sense of wide-open possibilities and the resolve to keep working.

Hers is the voice in my ear now, when I have doubts. “You just need to…” trim a little here, add a little there—not much, just a line or two, and don’t touch the ending. I can see her miming small adjustments, patting the essay into shape with her hands. I found that gesture so reassuring, and still do: her belief that the work is solid and real, close even, almost there. And so I keep working. And so, it is.

—Anne McDuffie, RWW Alum

***

Judith had been a 40-year-old MFA student at Warren Wilson, where she admired the writers but chafed at the petty hierarchies and occasional oppressions built into such a community. We each had decades of experience in writing education—the summer writers’ conference we co-directed for SUNY received an “A+” rating in a national guide. Judith served on the faculty at the Port Townsend Writers Conference, and we chose PLU as an attractive, well-located place for our dream, the first “low res” MFA in the Northwest. We had good support and got lucky. We learned the proposal had been passed—after two years of preliminary work—late one Friday afternoon in May 2003, sitting in our office in New York state. It was a joyous moment. We had talked, argued, planned, scribbled endless notes on napkins over many meals, imagining how it might be to have a program work in a different way, with true respect for the individual. No artificial ladders to climb or egos to placate to distract writers from the challenge of finding your own way. Everyone didn’t have to pretend to love everyone else, but the community needed not to be destructively competitive (something easy to fall into) or too prescriptively communal. A community of adults, based not on what you have been, but on what you might become. The Rainier Writing Workshop was born. But it needed the right participants (as we preferred to call them) to give it life. They—you, reading this—made it what it is.

Judith was my partner in everything, my critic, my support, my reason. The void—the silence—in my life is huge. But her words remain. There are two full books to come: her fourth Norton anthology of short nonfiction, co-edited with Dinah Lenney, and the collection of thirty years of her poetry reviews that Stephen Corey shepherded through the University of Georgia Press. As I write, I am filled with her words. I have just proofread the copy of her last essay, a gorgeous, passionate piece entitled “Breath,” forthcoming in River Teeth. It is filled with the shadow of impending death, but it is exquisitely lyrical and non-confessional. It is Judith at her best, intimate yet inclusive. Not worrying about honors or recognition, but going on to the next thing. In the last years, her repeated refrain was, “I have to be able to do this.”

I have never known someone who maintained such consistently high standards, yet was so unfailingly open and encouraging to other writers. Once when she judged a major national book prize, I witnessed her behind-the-scenes attempt to find publishers for two runners-up she believed in. She succeeded with one, the other did it herself after following Judith’s advice on revision. I recently found a letter concerning her late venture, Ovenbird Press, started in order to publish a set of RWW graduates whose work she especially admired. “I want to do one last thing for others,” she wrote. She contributed her remarkable novella-length essay from The Georgia Review, The Circus Train, to that effort to give it credibility, and she wrote introductions to these books under the label “Judith Kitchen Select.” I don’t believe she thought of herself as “generous.” It was just what should be done. It was who she was.

Weeks after she died, peacefully, instantly, in our bed, after directing me to tidy her closet (which I did), I sat at her computer surveying many folders of her essays, novels, reviews, panels, and talks. Even I was amazed at all she had accomplished—the more so because I knew the physical challenges she’d been coping with for several years and the immense work she did behind the scenes for the program, and then to effect its transition to a new director.

In her work and in her life, she was always in dialogue. Here’s the opening of her “mentor statement,” composed in 2007 for prospective students:

As a mentor, I try, first of all, to come to your material by taking my cues from the material itself. I think of my first job as discovering just what it is the piece (or collection) is trying to do. Then I think of how it can achieve its own goals. After that, I may think about its potential to go beyond that, into deeper or more complicated territory. And then I have to ask whether that’s appropriate to what it was trying to do in the first place. And so on, in circular fashion.

A long interview with Judith will appear in the Spring AWP Writer’s Chronicle, and I commend the special issue of Fourth Genre Kate de Gutes is editing on Judith’s contribution to literary nonfiction. She was a key figure in that genre’s rebirth, and perhaps its most important contributor of critical thought. So her words live and will. But her amazing human spirit lives on through all of you, RWW.

—Stan Sanvel Rubin, RWW co-founder, poet, husband

_

Photos courtesy of Sydney Elliott (1960 Diana camera, film)

_